They Died Far From Home

Honoring British sailors who were lost protecting the US coast during WWII.

During WWII thousands of British servicemen - soldiers, sailors, airmen - came to the United States. Most of them came here for training. Because in Britain in 1941 bombs were falling and the air was sometimes filled with Nazi aircraft, seven British Flight Training Schools (BFTS) were set up in the safe spaces of the US. Owned and staffed by US flight school operators, the BFTSs operated under Royal Air Force supervision and training followed the RAF flight training syllabus. The US Army Air Forces supplied the aircraft. Over 6,600 Royal Air Force pilots learned how to fly and how to fight in the air in the States.

Of those thousands of Britons in the US, over 423 never made it home. Most of those died in training accidents, but some British seamen came to fight the Nazis along the American east coast and died in combat there.

Combat? On the US eastern seaboard? Yes. Nazi U-boats (submarines) found very good hunting of merchant ships there. This was because the US was very unprepared for war, so much so that shipping along the US coasts carried on as if nothing was different. The U-boats came to the US eastern coastal waters to find that shipping was operating in peacetime manner along the usual shipping lanes and was unorganized, that is, not in defensive convoys or using zig-zag defensive maneuvering. There were also no blackouts along the seaside, providing strong night time silhouettes of the ships for the subs to target. In just the first two weeks of submarine warfare in US waters, 13 ships were sunk with most of them being tankers carrying valuable petroleum products. In June 1942 alone, U-boats sank 136 ships in American waters, totaling 637,000 tons. American defenses were so poor, so inadequate that U-boats could openly attack freighters from the surface in daytime. This went on for months and could easily be described as a massacre.

The U-boats also laid mines in strategic locations: the approaches to Boston harbor, and the mouths of the Delaware and Chesapeake Bays. Because of the inadequate reaction to threats, the mines worked.

To help overcome the glacially slow response to the attacks, the United Kingdom sent to the United States 24 fishing trawlers that were converted to anti-submarine warfare (ASW) boats. These trawlers came with their own crews - experienced seamen who, like their trawler, had been “requisitioned” by the Admiralty and converted into military assets. They were given 4” deck guns (or similar guns), as well as several .303 caliber Lewis guns and depth charges. They operated under the US Navy’s command.

By mid-1942, the U-boat threat was finally being taken seriously. Convoys were established and they had escorts of US destroyers and British ASW trawlers, as well as air support from the US Navy and US Army Air Corps.

At 5:02pm on June 15, 1942, over 50,000 beach goers in Virginia Beach and Hampton, Virginia, witnessed firsthand some of the bloodshed in the Atlantic. A convoy traveling from Key West to New York, KN-109, sailed through the minefield outside Chesapeake Bay which had been laid down two days earlier by U-boat U-701. The 11,600-ton tanker Robert C. Tuttle exploded, followed by the 11,200-ton tanker Esso Augusta. It was mistakenly thought that the ships had been torpedoed. Two more ships hit the mines in that same minefield. The 7,100-ton collier Santore capsized and sank in less than two minutes, and the British ASW trawler HMT Kingston Ceylonite, hunting for the suspected submarine hit another mine and also sank in less than 2 minutes with the loss of 18 British sailors.

The witness to war for Virginians and North Carolinians didn’t stop there. Ship wreckage washed up on shore all along the Outer Banks, as did bodies and parts of bodies of sailors from both sides.

There are four ships that are important to this story: HMT Kingston Ceylonite, HMT Bedfordshire, U-701 and U-558. I will tell you about each one before I tell you why they are so important.

U-701

The U-701 was a Type VIIC submarine, the workhorse of the U-boat fleet. It was commissioned and launched July 16, 1941, and was commanded by Horst Degen. On three patrols1, it sank or damaged 14 ships totaling 65,339 tons. These include the Robert C. Tuttle, Esso Augusta, Santore, and HMT Kingston Ceylonite, all victims of the mines it laid. On July 7, 1942, U-701 was attacked and sunk by an American A-29 Hudson flying from Cherry Point, North Carolina. Of the crew of 46, only Degen and six others survived.

HMT Kingston Ceylonite

His Majesty’s Trawler (HMT) Kingston Ceylonite was built in 1935 by Cook, Welton & Gemmell Ltd. for the Kingston Steam Trawling Co. Ltd. in Hull. It was requisitioned in September 1939 by the Admiralty, converted to military use, placed under the Royal Naval Patrol Service (RNPS) and loaned to the US in 1942. It displaced 448 tons and had a crew of 32.

On June 15, 1942, while escorting convoy KN-109 from Key West to New York, HMT Kingston Ceylonite struck a mine laid a few days days earlier by U-701. This occurred just off Virginia Beach, within sight of beachgoers. Three other ships had wandered into the same minefield. The US destroyer USS Bainbridge (DD 246), the Robert C. Tuttle and the Esso Augusta, both tankers, were all damaged. HMT Kingston Ceylonite sank. 18 of its crew were killed.

U-558

Like the U-701, the U-558 was a Type VIIC submarine. It was commissioned on February 20, 1941, and commanded by Günther Krech, one of the Kriegsmarine’s most successful U-boat commanders. Over the course of its 10 patrols, which kept it at sea for 437 days, the U-558 sank 19 ships totaling 116,000 tons. One of the ships it sank on its last patrol was ASW trawler HMT Bedfordshire off Cape Lookout, North Carolina.

U-558 also shot down an American patrol bomber, a B-24 Liberator, that was on anti-submarine patrol. The Liberator went down with all 10 crewmen lost. This was U-558’s last victim. Later that day, other anti-submarine bombers from the US Army Air Forces and the British Royal Air Force dropped multiple depth charges, sinking the U-boat. Of the 50 crewmen, only Krech and four others survived.

HMT Bedfordshire

The steam trawler Bedfordshire was built in 1935 by Smith’s Dock Company for the Bedfordshire Fishing Company. It displaced 443 tons and had a crew of 38. It was requisitioned by the Admiralty in August 1939, converted to an ASW trawler, and assigned to the Royal Naval Patrol Service. It patrolled British home waters until March 1942 when HMT Bedfordshire was sent to the United States to be placed under US Navy command and stationed at Morehead City, North Carolina.

On May 10, 1942, HMT Bedfordshire was dispatched with HMT St. Loman to search for a U-boat seen off the coast. At 5:40am on May 11, the U-558 spotted the Bedfordshire and fired a torpedo. That torpedo missed but a second one was fired and it struck HMT Bedfordshire which sank immediately. All hands were lost2.

When HMT Kingston Ceylonite and HMT Bedfordshire sank a total of 55 men lost their lives. For most of them, the Atlantic Ocean in US coastal waters is their final resting place. But for a few, their bodies washed up on shore. Some of those couldn’t be identified but some could. All of them, identified or not, were buried close to where they washed ashore, mostly along the Outer Banks. Their clustered burial plots became British cemeteries. These cemeteries were leased to the British government in perpetuity in 1976, effectively becoming British territory. The formal custody of the graves of all British war dead in the US is handled by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), which provides headstones and supports their maintenance.

In anticipation of the 80th anniversary of the end of WWII in Europe on May 8, 2025, the Commemorative Air Force (CAF), a living warbird museum like the Military Aviation Museum, started a project called “Bringing The Boys Back Home” to honor the sacrifice of these men. Grave rubbings of all 423 British servicemen’s headstones were made by volunteers across the US which would be flown by a CAF plane to Britain for the 80th anniversary celebrations. This would symbolically reunite the men and their families in the UK. The Military Aviation Museum handled getting the rubbings of the 42 graves in 12 cemeteries in Virginia and North Carolina.

So what is a grave rubbing? It is a technique to create a paper image of a gravestone. A piece of paper is placed over the stone and it is rubbed with charcoal or a crayon which leaves the engravings visible while the rest of the paper is colored in.

A very good visual story of the Military Aviation Museum’s part in this effort is at WAVY-TV. It shows the process of grave rubbing as well as the ceremony that was held turning over the rubbings to the CAF aircraft that would be bringing the boys back home. I highly suggest you watch it…it is well worth four minutes of your time. Follow this link: Volunteers honor British soldiers buried locally.

One local cemetery that has graves of British seamen is Oak Grove Cemetery in Creeds, a section of southern Virginia Beach, five miles south of the Military Aviation Museum. Four sailors are buried there, their graves maintained by CWGC. Those four are:

Alfred Dryden

Dryden was a Seaman aboard HTM Bedfordshire. Coming from Berwick-on-Tweed in Northumberland, England, he was the son of Jane Dryden and was married to Jane Anne. He died May 11, 1942 at the age of 32. His headstone has the inscription, “Father in thy gracious keeping leave we now they servant sleeping.”

John Ernest Farrall

Farrall was a Seaman aboard HTM Kingston Ceylonite. He was from Manchester, England and was the son of Robert and Caroline Farrall. He died June 15, 1942 at the age of 21. His headstone has the inscription, “Memories of his smiling face a broken link we can never replace.”

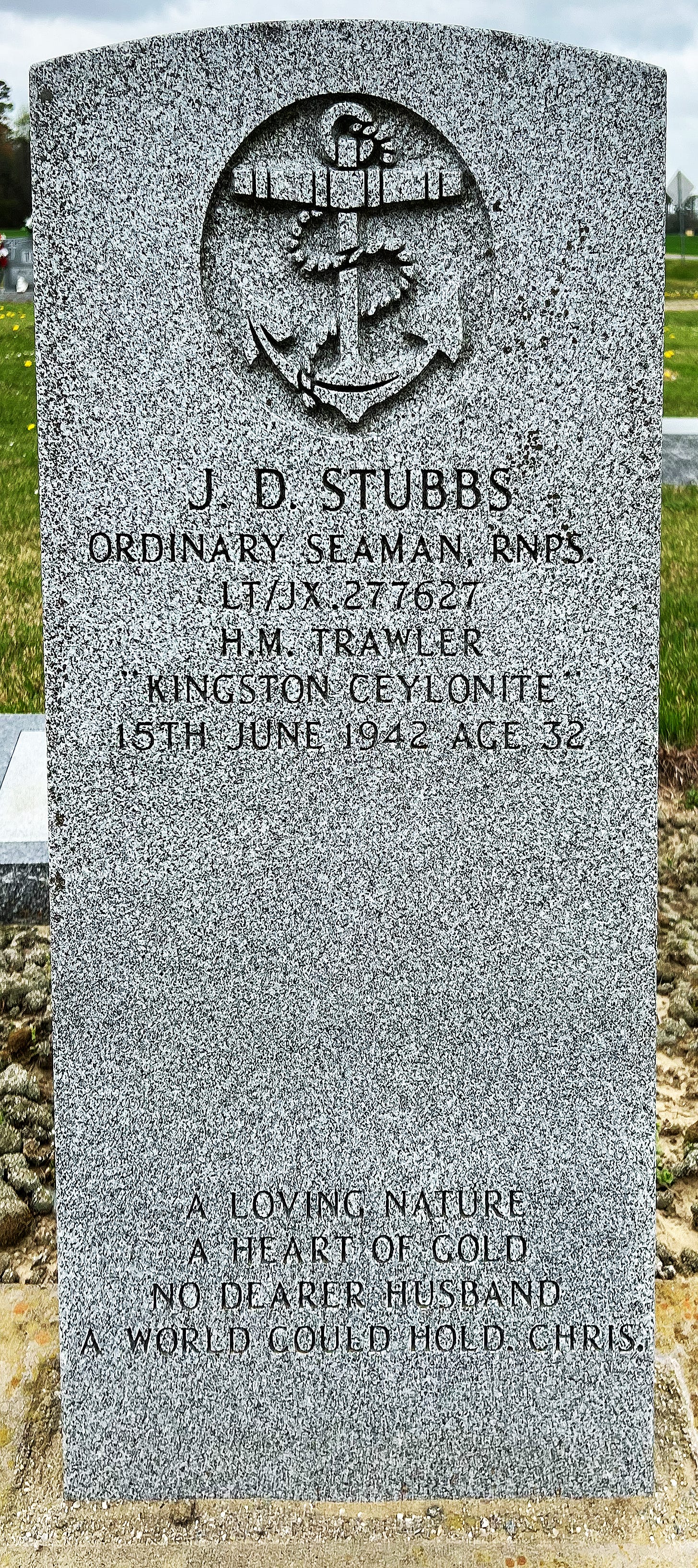

Joseph Davidson (JD) Stubbs

Stubbs was an Ordinary Seaman aboard HMT Kingston Ceylonite. He was the son of John and Jane Stubbs, husband of Christina and was from Lemington-on-Tyne, Northumberland, England. He died June 15, 1942 at the age of 32. His headstone has the inscription, “A loving nature, a heart of gold, no dearer husband a world could hold. Chris.”

Harold George Turner

Turner was a Seaman aboard HMT Kingston Ceylonite. He was the son of Samuel and Ethel Turner, husband of Edith, and was from Bedhampton, Hampshire, England. He died June 15, 1942 at the age of 30. His headstone has the inscription, “Faithful until death he has won a crown of life.”

The Missus and I volunteered to do the rubbings of those four headstones at Oak Grove Cemetery. As we were working the project became deeply personal. The Missus realized these were her countrymen who died thousands of miles from their homes. I was touched by the inscription on JD Stubbs’ grave when I realized it was written by his wife. We both fully appreciated that these weren’t just names on a stone…they were young men who had lives and loves, who laughed and cried, who had families and friends. Those families and friends said goodbye to them on docks in England, and never saw them again.

We were humbled and honored to help bring the boys back home.

2W:LYK

One member of HMT Bedfordshire’s crew, stoker Sam Nutt, had been in some sort of a dust-up and was detained by Morehead City police. As a result, he was not on board for his ship’s final voyage and was its lone survivor.