“Oh, Tim. That’s wonderful.”

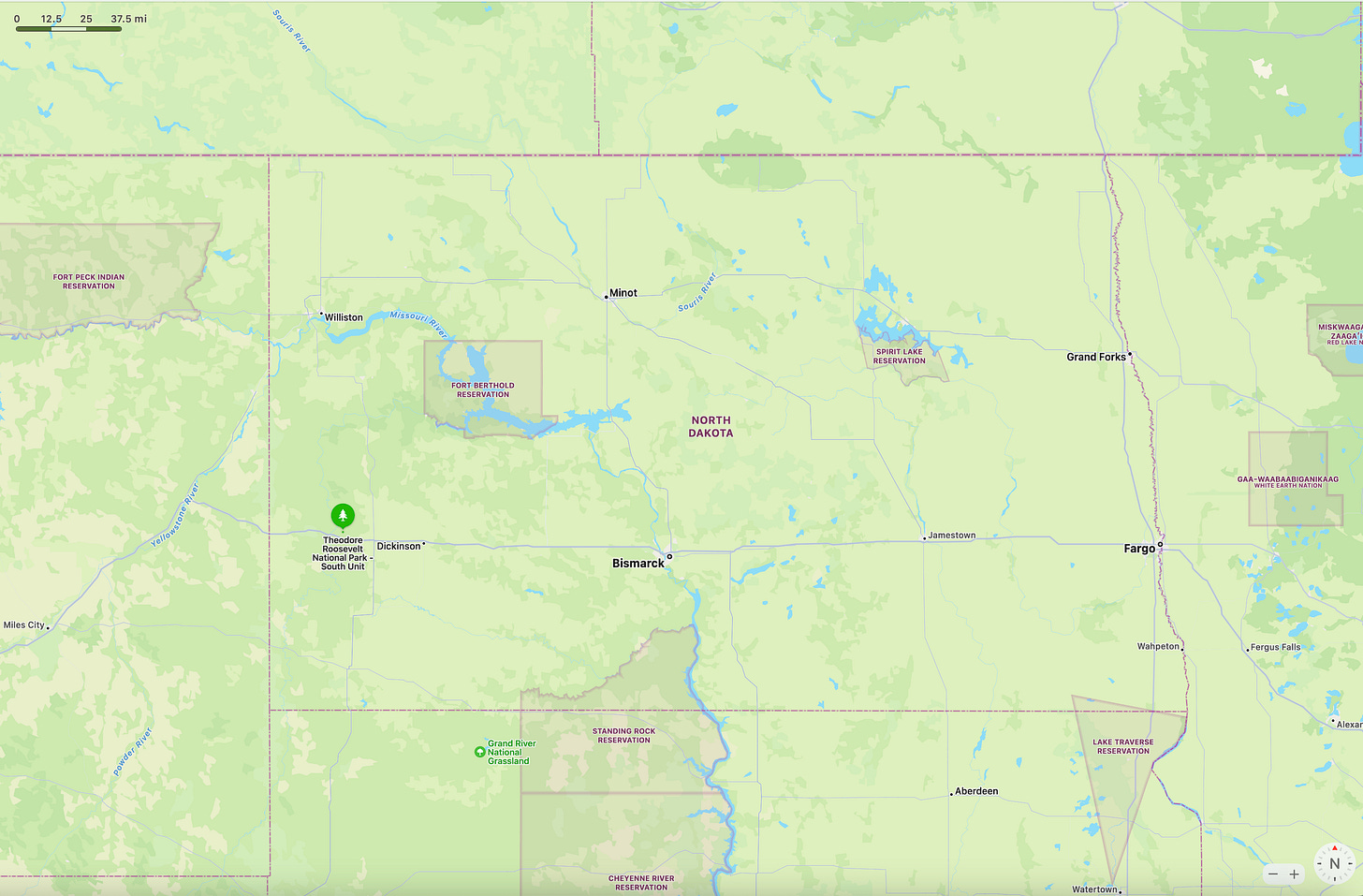

Those four words propelled me headlong into serious nature photography. I was taking my very first class in nature photography at Theodore Roosevelt National Park in the westernmost part of North Dakota. The class was being put on by a professional photographer named Pat Gerlach.

I met Pat at the annual Winterfair art show in Columbus, Ohio, in early December 2004. I saw a huge picture of a sage grouse in the snow, eating a rose hip it had just plucked from a nearly-denuded rose bush. As I looked at it closer, I realized that the picture was taken at the exact instant when the rose hip was suspended in mid-air, touching neither the upper nor lower bill of the grouse. Just then the photographer walked up. Still astounded, I said to him, “The timing of this picture is exquisite!” His response was not what I expected.

More than a few of the vendors at art shows – not all, but a substantial minority – would have responded to my comment with something akin to, “Ah, yes. I am the great artiste!” It’s a huge turn off for me and taints my perceived beauty of their work. But Pat, that wasn’t him at all. He thanked me (and was sincere about it), then to my astonishment, he started telling me about how he actually got the shot. He talked about needing to know your subject and its behaviors. In this case, he staked out the rose bush, knowing that at least one grouse would show up to eat. Then, he spoke of how he knew that the grouse would pluck the rose hip from the bush but then have to toss it around in its beak to get it in the proper position to swallow it. He took this picture when that was happening.

“So you knew you had it,” I said. “Not until I developed it in the darkroom,” he replied. “You see, with single-lens reflex cameras, when you press the shutter, the picture in the viewfinder disappears for a split second as the mirror flips up to expose the film, so if you see it, you missed it.” Without having sold me anything yet, he was teaching me.

We said a few more things and I finished looking at his work. I was impressed with all of it, and knew instinctively that his style was what I wanted my style to be, if I could ever develop it.

As Shelagh and I walked away I told her about Pat’s humility as compared to some of the other photographers we’d spoken to and how he actually took time to just casually teach me. She noted that she saw flyers in his booth advertising nature photography classes he teaches...and that I could go if that’s what I wanted for my birthday present. Did I ever! [Note: This is the reason I married her.] The following June I was staying in the AmericInn Motel in Medora, North Dakota, just outside Theodore Roosevelt National Park (TRNP) and the North Dakota Badlands.

The next five days were life-alteringly special. I learned a lot, not just from Pat and his instruction, but from the other students there, as well. Pat’s class was structured so that twice a day, every day, we all went to the same place at the same time and took the pictures we each wanted to take there. We then shared a few of our favorites at the end of each day. We discussed the strengths and weaknesses of each picture, as well as how we captured them. Most importantly, it allowed us to see the exact same location at the exact same time but through many different eyes. It was an amazingly effective technique.

For the first couple of days, my pictures were nothing special. I wasn’t one of the best shooters there, but I was learning and getting a bit better. Then one day we went to the Wind Canyon section of the park. As we were getting ready to head back to town because the early morning honey-tinged light was giving way to harsh mid-day sun, I saw a little yellow flower (a yellow goat’s beard, Tragopogon dubius, I later discovered) that looked like it needed to be photographed. I took the time to position myself so that my shadow cut down on the bright sunlight hitting the flower directly and took what I hoped would be an OK shot.

At that day’s review the goat’s beard was one of the pictures I shared. When it came up on the screen, Pat said, rather reflexively, “Oh, Tim. That’s wonderful.” He pointed out everything I did right, and nobody could find anything they would have done differently. I knew it then: I could be a nature photographer. And this is it, the photograph now titled, “Dakota Gold” that started my nature photography journey in earnest:

I have a couple of the other pictures I took that I want to share.

This picture of two bison cows and two calves (look between the cows) was taken at a really safe distance with a lot of zoom and cropping. I was standing still to ensure I didn’t tumble into the small ravine / large ditch between me and my bovine targets. But while I was standing on the shoulder of the road, I heard Pat announce, with a fair amount of authority, “This is about as close as we want to get to the bison.” I looked 90 degrees to my left to see Pat looking directly at me. I then looked 90 degrees to my right and saw an enormous bull bison, less than 30 feet (10 meters) from me. He had somehow come up out of the brush-filled ravine and stepped onto the asphalt without making a sound. And it’s not like there was any background noise to mask his approach - we were out in the middle of nowhere (that month, June 2005, TRNP had 3,700 daily visitors, so traffic is widely spread out over an expansive area and not a noise source). I didn’t stop to take a picture, pivoted left and quick-stepped towards Pat saying, “No. This is twice as close as we want to be!” I still have no idea how something so huge could move so stealthily.

Besides bison, there are a lot of other critters inhabiting TRNP. These include millions of prairie dogs, elk, mule deer, and the photographers’ main target, wild horses.

I did have a startling, non-photography revelation while I was there: Only when you see wild horses running free do you begin to really understand what all those songs and poems are going on about. It’s truly magical.

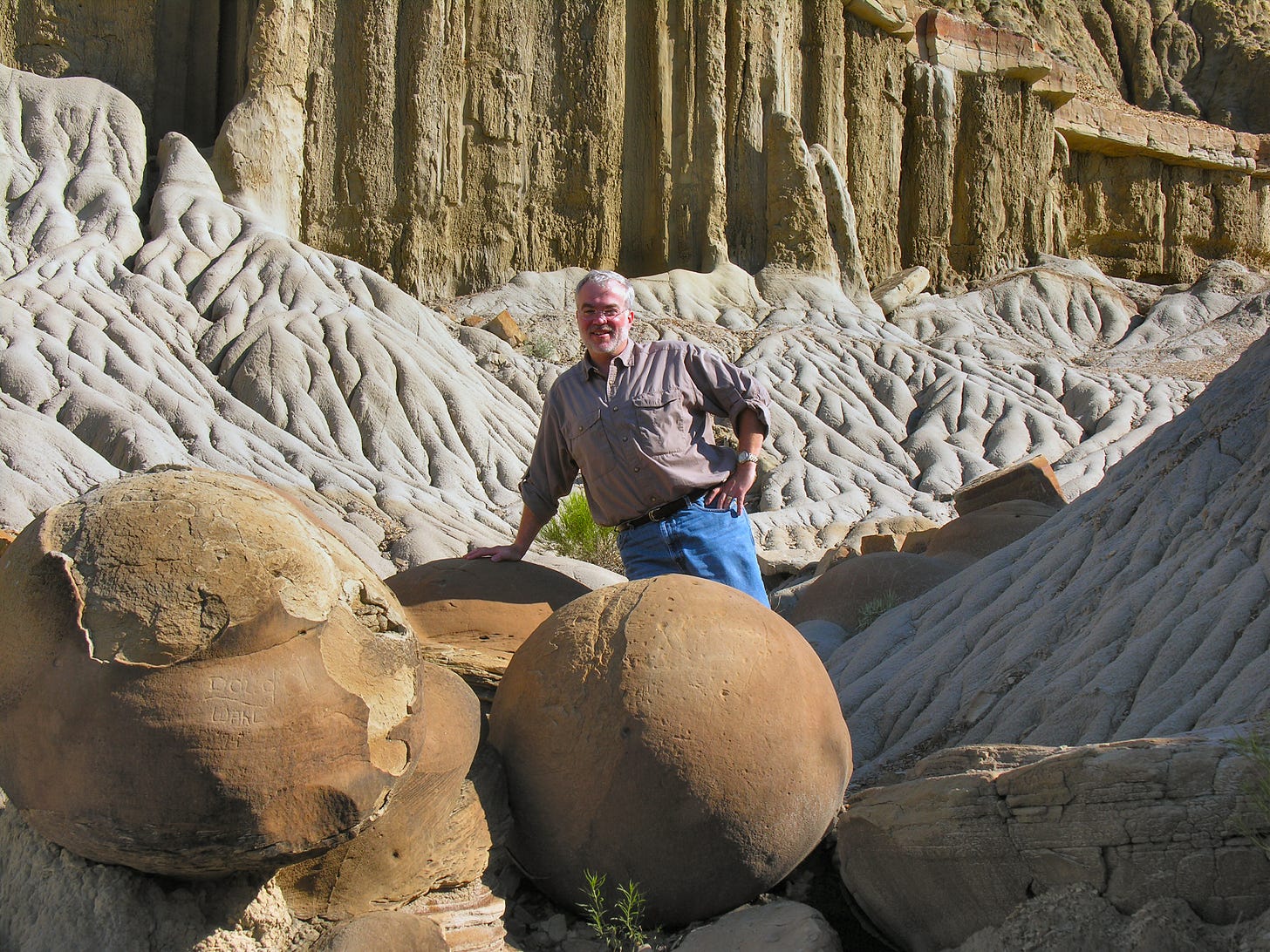

There is also lots and lots and lots of scenery.

I managed to get a couple of pictures of Pat, but none of his face. In the photo below, he’s making sure the students don’t get too close to the bison (and they aren’t as close as they look, a function of my zoom lens).

In this next picture, Pat is on a slight rise next to a parking lot. He is teaching us about, of all things, exposure, and why we may or may not want to shoot into bright light.

I learned an absolute ton of stuff about photography in those five days and had so much fun.

I met him again around 2010, once again at the Winterfair art show. We had a nice conversation and he was happy I had started getting good and getting a few awards for my work. The new pictures he had for sale were every bit as beautiful as his old photos that attracted me to his work.

A year or two ago I went to check out Pat’s website to see what new pictures he had posted and to revisit some “old friends.” It had been a while since I had gone to that site. It was no longer there…site not found.

I searched a bit deeper and found his obituary. He died of cancer in November 2018. I also found an article about his last art show. He knew he was dying and wanted to do one last one. It was at the July 2018 Fargo (ND) Street Fair where he had his first show 40 years earlier. A fitting close to a remarkable career.

I am blessed to have lived a life of very, very few regrets. As I sit here, looking at a dozen awards for my photography, including one from the National Center for Nature Photography, I regret that I wasn’t able to meet Pat again. I regret I wasn’t able to tell him what a profound impact he had on my life with four small words. By extension, he has had an impact on some of you. My desire to share the beauty and joy of what I’ve seen out in nature and hopefully make you more interested in the natural world is a result of his desire to do the same thing. We only met a couple of times but his absence is powerful. I miss him.

Rest in peace, Pat, and thank you.

2W:LYK

Oh, Tim. " Those are wonderful" and the story behind them is amazing!

Sweet tribute!